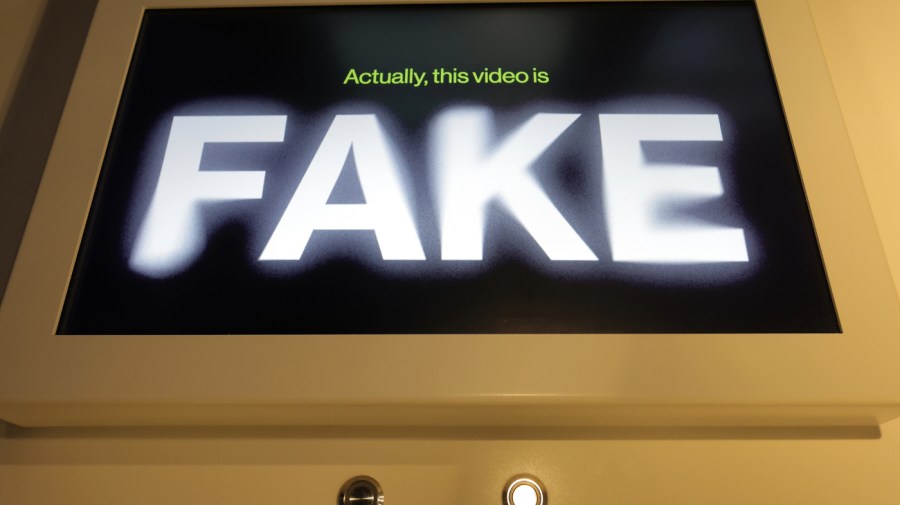

This week, former President Trump falsely claimed that images of a recent Harris campaign rally were fabricated by artificial intelligence — the first clear instance of a major American candidate sewing deepfake uncertainty.

Trump’s comments come on the back of an increasing tempo of deepfake deception, including someone’s ham-handed attempt to use generated audio of President Biden to sway the New Hampshire primary and a perhaps more impactful use of deepfakes to influence Slovakia’s October election. Meanwhile, xAI is rolling out an astounding new model that enables remarkably realistic, unfiltered imagery.

Just as AI is creating institutional uncertainty, the tech is zooming ahead.

The challenge of trust and authenticity in an era of highly capable deepfakes should not be understated. The potential electoral strains are familiar by now, but few have fully grappled with how serious the strain could be on other facets of society.

During a trial, for instance, what’s to stop a criminal from introducing generated security camera footage to clear their name, or crying “AI!” when damning audio evidence is introduced? Baseline expectations of authenticity not only inform democratic institutions but are deeply woven into the basic rule of law.

Beyond the courtroom, synthetic media is actively being used to defraud. In 2023 alone, Deloitte estimated that generative AI enabled the pilfering of $12.3 billion, a figure that will no doubt increase as capability improves. Deepfakes are growing powerful and a tipping point of trust may be near.

The bad news is that shouting for a catch-all “solution” isn’t the solution. There are no easy answers and no simple legal text can swat this growing problem. This tech is out there, in use, and scattered across hard drives and the internet. Instead of hoping for a clean regulatory fix, what we need now is triangulation.

The good news is that partial solutions exist. The first and most important step is developing and deploying a slate of reliable, easy-to-use forensics techniques to provide a technical basis for ground truth. Already we have a decent first step: watermarking technology. When used, this tech can embed content with signatures to verify authenticity. Use, however, is inconsistent.

To augment watermarks, we will also need to develop a suite of standardized, easy-to-employ and easy-to-verify content authenticity techniques, perhaps involving a mix of automated deepfake detectors, learned best practices and contextual evidence. Thankfully, research is already underway. However, things need to be both accelerated and sustained over time as the tech keeps pushing forward.

To get this done, policymakers should consider authorizing a series of AI forensics research investments and grand challenges, with the recognition that it requires a long-term commitment to ensure tools keep up with quick-moving technical evolution.

With tools in place, the second step is to that ensure institutions at all levels of society are equipped to wield them, and consistently.

While the bulk of the deepfake discussion has focused on threats to federal electoral politics, the depth of impact is most likely to be felt in local politics, institutions and courts which lack the institutional capacity and civil resources needed to vet and navigate authenticity questions. Simplicity, consistency and clarity are key.

Federal standards-setting bodies can help by commissioning approachable standards of practice intentionally designed to accommodate low-resource, low-knowledge local actors. States, meanwhile, should fund outreach to educate and promote the use and integration of these processes and standards.

The final, and perhaps the most actionable step right now, is more education. In the immediate term, there will be considerable confusion, fraud and deception due to what Professor Ethan Mollick of the Wharton School recently termed “change blindness.” The public’s understanding of generative AI’s evolution significantly lags behind the breakneck state of the art.

A quick scan of internet comment sections suggests many either cannot identify obviously generated media or assume that outdated rules-of-thumb — such as the presence of too many thumbs — remain meaningful. The bar for deception is low.

Here, simple PSAs could go a long way. Already the Senate is considering the Artificial Intelligence Public Awareness and Education Campaign Act, which would sponsor a campaign of such PSAs. While a one-shot campaign can help, policymakers must be prepared to make this continuous and mitigate change blindness as the technology improves.

All of these steps would help. Through a triangulation of efforts, policymakers and civil society can hopefully seed the ground with tools, institutions and understanding needed to encourage trust. The bulk of action must ultimately fall on the backs of civil institutions to create critical, socially driven norms to push society towards a comfortable new normal.

That said, to ensure trust is preserved on the path to that new normal, immediate effort and institutional action are needed today.

Matthew Mittelsteadt is a technologist and research fellow with the Mercatus Center at George Mason University.