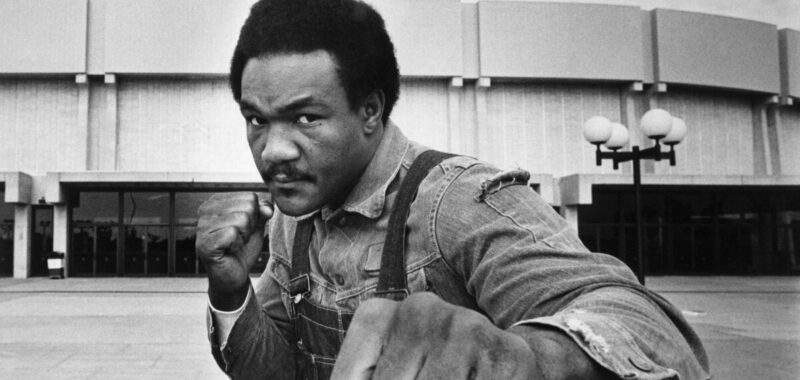

George Foreman, the sleek, surly boxer who tangled with Muhammad Ali in the epic “Rumble in the Jungle” heavyweight championship fight before embarking on a lifetime of reinventions as a minister, youth counselor, cookbook author and TV pitchman for his own line of big and tall menswear, has died.

As bubbly in the spotlight as he was ferocious in the ring, Foreman died on Friday, his family announced in a social media post. He was 76.

“A devout preacher, a devoted husband, a loving father, and a proud grand- and great-grandfather, he lived a life marked by unwavering faith, humility and purpose,” his family wrote on Instagram.

Although Foreman was best known for his accomplishments in the ring, he also was a successful entrepreneur. He was so successful at promoting the George Foreman Lean Mean electric grill that an entire generation grew up recognizing him as the television grill guy, little knowing and little suspecting that he had ever been a boxer, much less a two-time heavyweight champ who won 76 of his 81 fights, 68 by knockout.

“People trust me,” Foreman once told USA Today of the zigs and zags in his colorful and varied career. “I sell sincerity.”

Along the way, he married five times and had at least 12 children. He named all five of his sons George, assigning each a number and a nickname, explaining on his website: “I named all my sons George Edward Foreman so they would always have something in common. I say to them, ‘If one of us goes up, then we all go up together, and if one goes down, we all go down together.’ ”

He didn’t start out being George Foreman. His biological father was Leroy Moorehead, but his mother married J.D. Foreman when George was a toddler, and raised him, along with six siblings, as a Foreman.

His was not an idyllic childhood. Embarrassed at living in chronic poverty — his school lunches often were mayonnaise sandwiches — he set out to remedy the situation, shoplifting, intimidating students for their lunch money, mugging people in the street. He once said his goal was to go to prison, then build the fiercest gang in his hometown of Houston.

“I was a bad guy, badder than anything you can imagine,” he told Newsday in 1991. “I was a real bad boy.”

One day when he was 16, fleeing police after another mugging, he crawled into a house excavation. It had been raining and the ground was muddy. Foreman wallowed in the mud, hoping to throw off the scent of any dogs the police might be using in their pursuit, then lay still, thinking. Stinking of the filth he’d rolled in, he concluded that he was probably on the wrong path.

“You are one gutter rat,” he said he told himself.

Not long afterward, he saw a TV commercial for the Job Corps and persuaded his mother to sign him up. There, he earned his GED diploma, learned bricklaying and carpentry, was introduced to boxing and visualized a real future.

“I was rescued by a compassionate society,” he said.

Instead of putting his newfound skills to work, though, he chose boxing, moving to the Bay Area for training. Slow but methodical and possessing a wicked knockout punch, he advanced through the amateur ranks, qualifying for the Summer Olympics in Mexico City in 1968.

There, in the Games famous for Black power protest salutes by track stars Tommie Smith and John Carlos from the medal stand, Foreman bloodied Lithuanian Jonas Cepulis, fighting for the Soviet Union, for 1½ rounds in the gold-medal heavyweight match, winning when the referee stopped the fight. Then, to the dismay of Black activists who used the Games as a platform to protest systemic racism back home, Foreman paraded around the ring waving a miniature American flag.

As an amateur, Foreman had sparred with former heavyweight champion Sonny Liston, and when he turned pro, it was with Liston’s management team, Foreman assuming Liston’s fierce demeanor in the process.

“Well, we’re all a product of our heroes,” Foreman told Newsday. “You want to be like your heroes, but before you know it, you’ve bypassed being like them. You become them.”

Thus, a very unpleasant Foreman scaled the heavyweight division, getting his shot at champion Joe Frazier in Kingston, Jamaica, in January 1973. A decided underdog, the unbeaten Foreman nonetheless dominated, knocking Frazier down six times and winning on a technical knockout in the second round amid Howard Cosell’s excited call: “Down goes Frazier! Down goes Frazier! Down goes Frazier!”

Twenty-one months and three fights later, he was an ex-champion, because of Muhammad Ali, himself a former champion. Ali had dominated the heavyweight division in the mid-1960s but was stripped of his title belts and banned from boxing after refusing to respond to the U.S. military draft during the Vietnam War. By 1974, after four years of forced exile, Ali was back in boxing’s good graces and on the comeback trail, hungry to regain the championship.

Ali had recently beaten Frazier to earn a shot at Foreman, but he was also 32 and no longer the ringmaster whose speed and power mesmerized fans. Still, the match was made, “The Rumble in the Jungle,” in Kinshasa, Zaire, now the Democratic Republic of the Congo, with Foreman a formidable favorite.

Ali attacked in the first round and, in the second, fell back against the ring ropes, inviting Foreman to hit him, taunting, counterpunching, clinching, covering up, deflecting Foreman’s thunderous punches in a unique style he later called “rope-a-dope.” As the fight wore on, a frustrated Foreman began to tire and Ali began landing punches. He connected with a combination in the eighth round, Foreman went down for the count, and Ali was, once again, the heavyweight champion.

“I thought Ali was just one more knockout victim until about the seventh round,” Foreman said later. “I hit him hard to the jaw, and he held me and whispered in my ear, ‘That all you got, George?’ I realized that this ain’t what I thought it was.”

Foreman won his next five fights over a three-year span, then signed to fight a rising Jimmy Young in Puerto Rico. Ignoring advice to move his training site, Foreman flew into San Juan the day before the fight then, on a hot day in a building with no air conditioning, fought sluggishly for 12 rounds before being knocked to the mat. He lost on a decision.

In his dressing room after the fight, suffering from exhaustion and heatstroke, Foreman collapsed and thought he had died.

“If there’s a place called ‘nowhere,’ this was it,” he later wrote. “I was suspended in emptiness, with nothing over my head or under my feet.… I knew I was dead and this wasn’t heaven.” He said he began to plead with God to help him and when he said, “I don’t care if this is death, I still believe there is a God,” he felt a hand pulling him out of his ordeal.

He never announced a retirement but quit fighting and began preaching, on street corners at first, then, after ordination, in his own Church of the Lord Jesus Christ in Houston. He also opened a youth center and, for the next decade, dedicated himself to helping others, losing all of the fierceness he’d adopted as a fighter.

Eventually, though, expenses, questionable bookkeeping by associates and bad investments ate his savings, and in 1987, at 38 and weighing nearly 300 pounds, he announced, to the mirth of many, his comeback.

And he made it work. His punch was still there, and, lining up a string of stiffs to ease the way, he gradually fought himself back into reasonable shape, losing to name fighters Evander Holyfield and Tommy Morrison, but finally getting another crack at the title against Michael Moorer at Las Vegas in 1994.

It quickly became obvious that Moorer was the superior boxer, and after nine rounds, he was far ahead on points, leaving Foreman one chance — a knockout. One chance was enough. He hit Moorer with a left in the 10th, then followed it up quickly with the thunderous right, and Moorer was gone. Foreman, at 45, had become the oldest heavyweight champion.

“George was a great friend to not only myself, but to my entire family,” Top Rank president Bob Arum said. “We’ve lost a family member and are absolutely devastated.”

He successfully defended the title three times before losing it to Shannon Briggs in 1997, and then, at 48 and having made more money the second time around than he’d made the first time, ensuring the continuation of his church and youth center, he finally retired.

The marketing world, however, had discovered the new, people-friendly George Foreman, and soon other opportunities were coming his way, the biggest, as it turned out, the grill. Since Foreman began touting its drain-the-grease benefits, it has sold more than 100 million units, and counting, worldwide.

After making about $60 million on the original deal, Foreman sold his naming rights back to the company for $137.5 million, continued proclaiming the grill’s superiority and carried on with his various other lucrative activities. As of 2022, Forbes put his net worth at more than $300 million.

In 2022, two women sued Foreman, saying he sexual abused them as teenagers after “grooming” them as children. Another woman filed a lawsuit against Foreman in 2023 accusing him of sexual battery against her in the 1970s. Foreman denied the allegations.

Late in life, Foreman and his wife, Mary, retired to a 45-acre compound in Huffman, Texas, where he had basketball and tennis courts and a garage packed with 38 cars. On weekends, they’d head to their ranch in nearby Marshall and go horseback riding and tend to the black Angus cattle they raised for their mail-order meat company, his latest enterprise.

“Money has to be spent,” Foreman told Sports Illustrated during a visit to his cattle ranch. “It is not made to be saved.”

Kupper is a former Times staff writer.

Former staff writer Steve Marble and the Associated Press contributed to this report.